"Anyone who uses medicines ought to contribute the knowledge they acquire to help future users. Let's bring Care & Research closer together," says MEB chairman Prof. Dr Ton de Boer. He claims that more research is needed into the favourable effects of medicines. Although this research should be carried out by scientists, input should also be provided by experts from the field or, in other words, the medicine users.

When assessing medicines the MEB always looks at the proof that indicates whether a medicine works, or weighs up the effect against the adverse reactions. "This proof has to be convincing and preferably obtained via standard randomised studies. A lot of thought is going into new types of clinical trials. Some are already being used. In the case of Adaptive Trial Design a study structure based on interim analysis can be adapted, for example by terminating, or indeed increasing, participation by patients with certain characteristics in one or more study arms. We are also seeing Single Arm Trials more and more frequently, for example in conjunction with oncology medication, whereby a pharmaceutical company tries to accelerate the authorisation of a medicine on the basis of phase 2 studies. However, this is something we at the MEB find very difficult because there is then no control group for a direct comparison."

No 'light assessment'

Ton De Boer recognises that this sounds contradictory. After all, on the one hand the MEB wants to make new medication available to patients quickly while, on the other hand, it puts on the brakes. "Yes because the effect has to be proven and safe. So that requires certain studies and that will always be the case. Patients have to be able to have confidence that, if we authorise a new medicine, the benefit-risk balance is positive. This means that, if possible, large-scale studies are always needed in phase 3. And yes, we're always asked to do it more quickly. And sometimes that's possible. However, there will always have to be convincing proof. That is crucial." He refers to the example of the classical form of Pompe disease, which is a muscular disease that affects children. "In that case the effect of a new medicine called myozyme was so convincing that you just know it's going to work. Because without the medicine you know what the natural progression of the disease is, namely that these children will, on average, die around their first birthday. A control group is then less important when it comes to determining the effectiveness. However, it continues to be a combination of thorough, but also efficient and effective research. Ultimately the proof has to be sufficiently convincing. We don't do any 'light assessment', but we are, however, realistic."

Care & Research

The MEB chairman believes there are opportunities for extra research, once a medicine has been authorised and is being prescribed: "As soon as the medicine is authorised, we ought to study not only the adverse reactions, but also the favourable effects of medicines systematically and in a valid way."

A type of research which has not yet been used very often, called the Pragmatic Trial, could play an important role, Ton De Boer believes. The idea is that medicines with the same indication are given to patients in a randomised way in everyday practice, for example if you want to compare two statins. The randomisation is arranged via the prescriber and ought to take place in an environment where patients are routinely monitored via 'Electronic Healthcare Records'. This structure enables the favourable effects in the long term to be studied as well and in patient groups which were excluded from the preauthorisation studies. One problem with this type of studies is the obligatory informed consent in the event of randomisation. Research has shown that the informed consent results in doctors and patients being reluctant to participate. In, among other places, America and Canada a Pragmatic Trial can be carried out in certain circumstances without informed consent. Among other things this is also a case of equipoise, in other words uncertainty on the part of the doctor, patient and researcher regarding the outcome of the study because it entails the comparison of two or more interventions of which the relative benefit-risks of the medicines is unknown. Recently Ton De Boer and other co-authors argued in the BMJ that the regulations should be altered in Europe as well. The Pragmatic Trial can, therefore, bring Care & Research closer together.

Ton De Boer refers to the example of this being done via so-called 'academic GPs', or GPs who cooperate with studies. "The patient knows in advance that his GP is helping with the studies and if the patient does not want to cooperate with a clinical trial, he can indicate this in advance. The following is an example. The doctor establishes that his patient has to start using a cholesterol-lowering medicine, i.e. a statin. You could then carry out a pragmatic study. These days we have a choice of 5 to 6 good quality statins in the Netherlands. So you can have fate determine which statin the patient receives. And if you randomised this data, you can routinely collect information on morbidity and mortality. This will give you an insight into the effects in the long term. That would be a hugely interesting study. After all, everyone gets the care he should get, the patient will be unaware of the study and we will be able to gather a huge amount of knowledge about the relative favourable effects. We will be creating a longer follow up and we can also assess therapy compliance. Although trials do focus on therapy compliance, things are different in everyday practice. What then are the effects? I believe there are enough reasons to collect information on the favourable effects and to study them."

The question is who is going to carry out and finance such studies in the future. The MEB can, in any event, highlight their importance. Ton De Boer thinks that a lot of people realise how important these types of studies are: "And the MEB will then receive a lot more information which is valid and can, if necessary, be used to change the product information relating to a medicine."

Real World Data

Ton De Boer also thinks that this kind of Real World Data could play a much more important role in the pre-authorisation phase. "In the case of phase 3 clinical studies you could not only carry out studies using data which is collected on the basis of strict protocols, but also data which is routinely collected in the healthcare sector. The patient may, of course, also visit his GP or specialist outside the context of a study if he experiences illnesses and symptoms. The medical data which is then recorded could enrich the clinical study data. Data collected using health apps, such as step counters or heart rate monitors, could be used to monitor the impact of a medicine on, for example, a patient's stamina. There is, however, still some way to go for such data can be used in a meaningful way. We still have to discover how valuable this is. It may well enhance the phase 3 studies, but also be useful thereafter in terms of gaining more of an insight into the favourable effects of medicines." Real World Data can also be used to clarify more effectively the results of the above-mentioned single arm trials in the context of oncology by comparing outcomes with a relevant Real World population.

"It is logical, as regards Real World Data, to look to link up with Health Technology Assessment (HTA) organisations. They too have a clear need for Real World Data to be used via registries."

The future

It is important for the further access and use of Real World Data in the pre-authorisation phase and thereafter for possible label changes that the MEB cooperates at both national and international level. As Ton De Boer explains, "We are doing that with universities, the National Health Care Institute [Zorginstituut Nederland] (ZIN), the Regulatory Science Network Netherlands (RSNN) and relevant parties within Europe. The MEB fulfils a pioneering role in the EMA Task force on Registries, and also participates in the HMA/EMA – Task force on Big Data. In addition it is important to consider focusing the MEB's scientific policy more on research into Real World Evidence. Cooperation is already taking place with, among others, Utrecht University, Erasmus University Rotterdam and the University of Groningen via PhD programmes in this field."

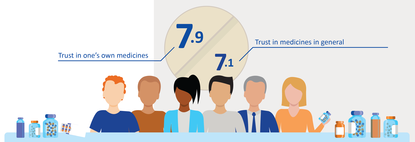

Ton De Boer believes that the extra information via RWD could further improve patient confidence in medicines. "It is relevant for patients if they know more about their medicines, what the impact is in everyday practice, what they stand to gain and what the adverse reactions are. This will increase confidence even more, even though there is, of course, always the possibility of us discovering that the balance between effectiveness and safety is poorer in everyday practice than we thought during authorisation.”

See also the summary of the 4th RSNN Workshop 2019 – “The future of clinical trials and evidence generation, and their use in regulatory decision making” – where prof. Ton de Boer gave a presentation.